A few months ago, I received an invitation for a dream gig. Simon Fraser University at Burnaby, British Columbia is designing a master plan to guide the institution for the next 50 years, and they needed an education futurist to provide some thought leadership.

The construction of the Burnaby campus is a legend among futurist circles. Creation of SFU was legislated in 1962, and, by 1965, the campus at Burnaby was conceived, built, and opened its doors to students — a seemingly impossible feat. Arthur Erickson won the bid to oversee the architectural design and construction of the campus, creating a space that was radical for its time: breaking up individual, siloed buildings for faculty and classrooms in lieu of spaces where different faculty and students would regularly encounter each other. In a taped session with SFU’s association of retirees, Erickson and partner architect Geoff Massey said that they got away with it because the university was designed before any faculty members were hired who could provide guidance.

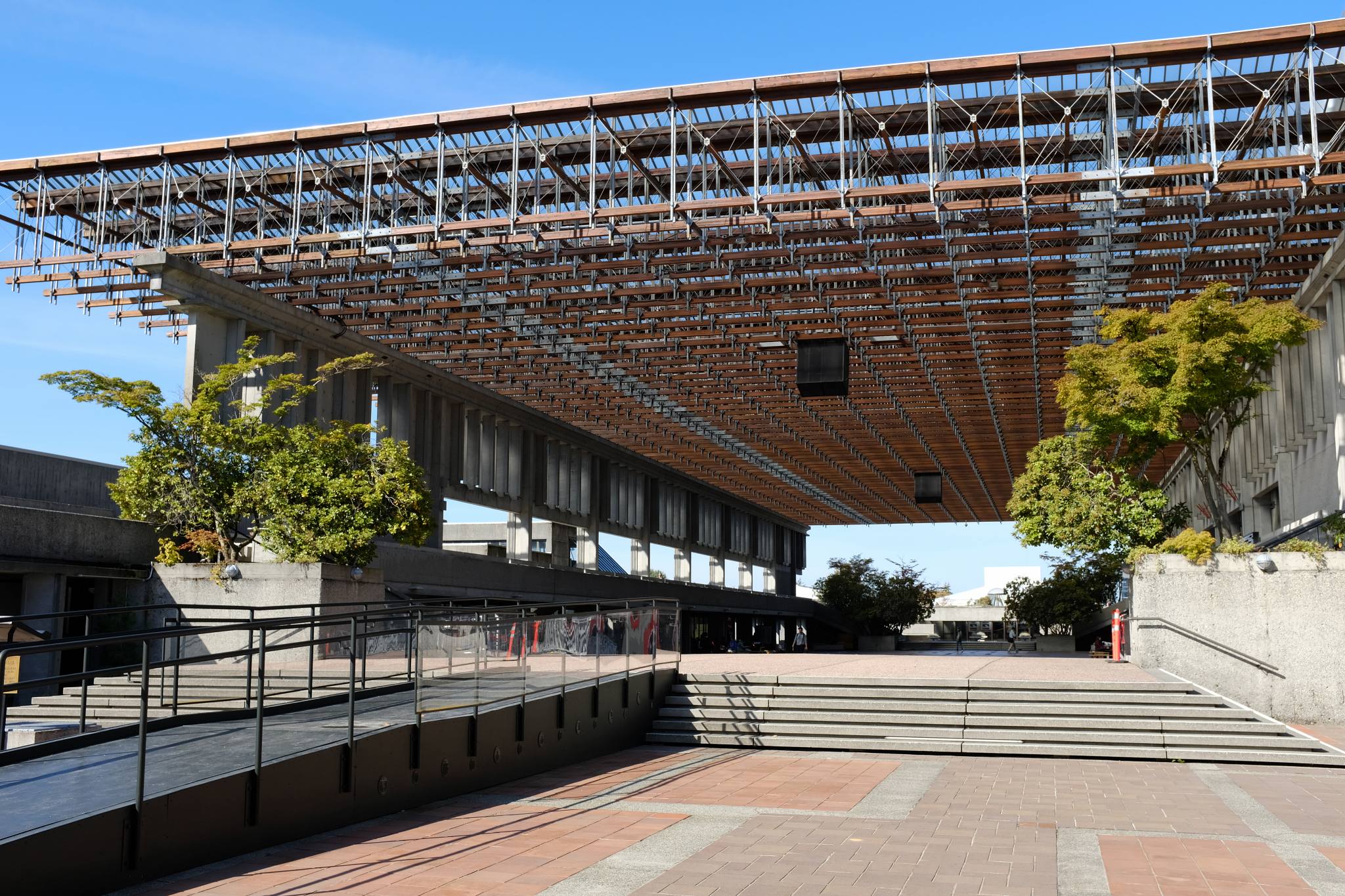

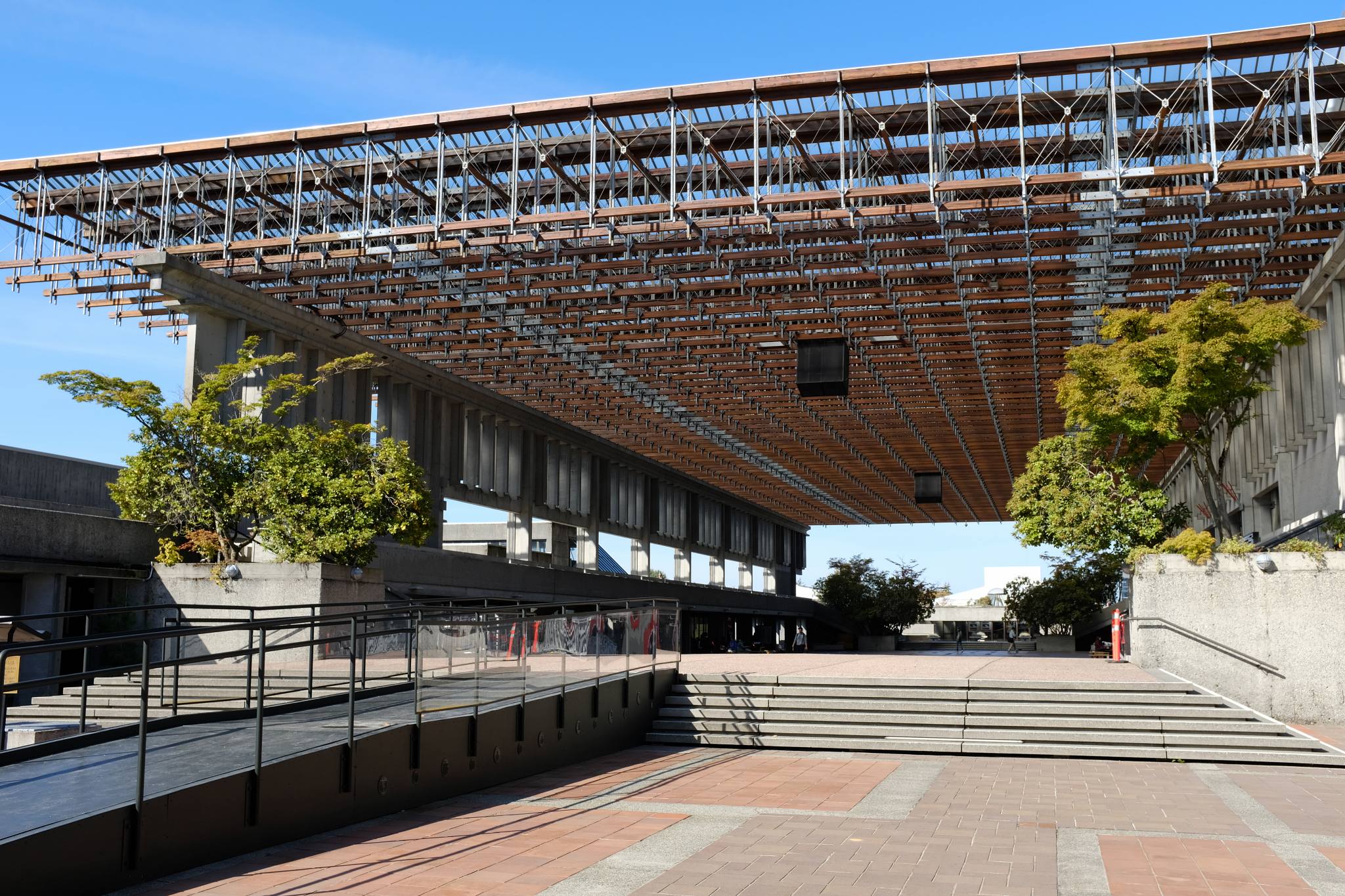

Erickson’s design is an enigma. It is unapologetically brutalist; poured concrete that is cold, authoritarian, incredibly hard to rethink with its concrete corridors and broken grading, and only seemed to amplify the chilly, grey weather that the Vancouver area is famous for in the winter months. At the same time, the layout of the campus was designed to serve interdisciplinary roles, bringing people together. Even through the concrete walls, there’s a certain sense of transparency that the architecture provides as you walk along its east-west axis. There is a real human element to it. And it reaches a crescendo at Convocation Mall.

Erickson’s task was to build a campus that would be as relevant 50 years in the future as it was in the 1960s, and they succeeded. The result, however, is that it looks like a future that has been around for a long time. It’s no coincidence then that the campus has been featured in science fiction television shows and movies — most notably depicting the post-apocalyptic, nuclear wasteland of Caprica in Battlestar Galactica (and some pre-apocalyptic scenes, too).

That worked well on television, but it can be tough for the student experience. When I crossed the border into Canada, a guard asked me, “what are you going to do at SFU Burnaby?”

I responded, “I’m going to help think about what the campus will look like in the future. Did you go there?”

“Yes, a bit.”

“What did you think of the campus space and buildings when you were a student?”

“I think they could be torn down.”

Ouch.

Love it or hate it, it's built to last. There is a lot of poured concrete. Personally, I like it, perhaps because the campus projects a certain vision of the future while creating a vibe that is very honest and authentic. It is a modern acropolis. The buildings designed by Erickson and Massey serve a purpose; nothing is pretentious. Would I enjoy studying or working among these cold, grey buildings on a cold, grey, winter day? That could get tough. The challenge is to preserve Erickson's vision while making the campus relevant and attractive for the next 50 years.

Looking forward…

SFU is looking to renew its vision for the next 50 years, building new spaces, while preserving and adapting Erickson’s vision and work to meet a new mission.

In a technology-driven world, what can the university do that technologies won’t be able to do?

Toronto-based Urban Strategies Inc. is leading the process to complete the master plan, building upon experiences they had for communities such as Princeton University and the City of St. Paul. The process is summarized on their website at SFUburnaby2065.ca.

At SFU’s public event on envisioning the Burnaby campus on September 18, I shared that, to me, the university of the future needs to look more like a festival — a gathering space. I don’t mean a festival like a big party, but a festival where:

- People from diverse backgrounds come together and share;

- It is a fundamentally creative space - to learn, work, live, and play;

- Serendipity is enabled. Not everything is pre-programmed;

- Self-organization by students to discover and learn what is important for their own individual development. I think this goes beyond instructor-student co-creation as students need to become the source of their own learning direction;

- Movement is rapid: you follow the flows of your own interests. Groups of people form their own seminars;

- It’s not just a formal experience. There are many other, ‘invisible’ ways of learning that are attended to; and,

- Space is used fluidly (and designed fluidly) to allow for flexibility and repurposing.

The qualities of a festival mirror those that are needed for an organization such as SFU to thrive well into the future. Adapting the shift in paradigms I discussed in our book, Knowmad Society (and built as an extension to work by Schwartz & Ogilvy, 1979), we arrive at so what? conclusions for what this means for the university of the future, and, in particular, SFU as it builds a master plan to remain relevant in 2065 (Moravec, 2013, p. 40):

| Domain |

Traditional paradigm |

Knowmadic paradigm |

SFU Burnaby 2065: the university of the future |

| Fundamental relationships |

Simple |

Complex creative (teleological) |

Facilitates creativity |

| Conceptualization of order |

Hierarchic |

Intentional, self-organizing |

Empowers all stakeholders to create change |

| Relationships of parts |

Mechanical |

Synergetic |

Builds relationships; enables serendipity |

| Worldview |

Deterministic |

Design |

Enables design |

| Causality |

Linear |

Anticausal |

Adapts, reacts, and pre-acts |

| Change process |

Assembly |

Creative destruction |

Agile; capable of reinvention |

| Reality |

Objective |

Contextual |

Crafts applications |

| Place |

Local |

Globalized |

Engages the world |

In an age of constant change, we need to enable people to become who they dream to be, creating new roles and pathways through life. The university of the future needs spaces that provide for high agency and high self-efficacy. High agency spaces get rid of top-down dynamics, enabling everybody bring their best. Agency is being afforded the space to do what you would like to do or learn. Self-efficacy is the ‘can do’ belief in ourselves to make this learning or doing happen. (See my TEDx talk on invisible learning for more on bringing agency and self-efficacy into education.)

Spaces that afford the development of self-efficacy are safe, comfortable, and permissive of failing... while helping to provide the resources so that none of us become failures. These can be expressed through:

- Laboratories

- Experiential learning

- Interculturally-focused, and new-culture-generative experiences

- Simulations and games

...and so on. Many of these are explored in greater detail in the 'Leapfrog University' series.

Noriega et al (2013) contributed an excellent article on design orientations for a special issue on knowmad society in On the Horizon. They wrote learning institutions must become:

- Agile and adaptive

- Activity-oriented

- Comfortable and safe, but challenging by attending for the creation of the unexpected

- Signifying membership, collegiality, us-ness

- Playful and seductive

- Affordable

Libraries are figuring out how to become agile and adaptive. Think how much libraries have changed over the past 20 years, with particular thanks to the growth of digital technologies! At SFU, original Erickson and Massey design afforded the mixing of different departments — they wanted to facilitate interdisciplinary work. This is great, but future trends toward individual-level knowledge production suggest that we should try even harder. Interdisciplinary environments will no longer be sufficient. We need spaces (and other university structures) that help facilitate transdisciplinary learning and discovery. Enabling serendipity is probably the best way to make this happen.

Activity-oriented (not delivery-oriented) universities are focused on new knowledge production and discovery, not industrialized, mass-delivery. As we move forward into this age of accelerating change and uncertainty of what the future may bring, we need to invest in teaching and learning approaches that go beyond ‘download’ or ‘banking’ pedagogies. The university community of the emerging future needs to co-create new knowledge together.

We need to de-emphasize top-down learning spaces such as classrooms — and we need to focus on creating spaces where everybody can participate: laboratories, co-working/co-studying, spaces that attend to seminar-like experiences. At the moment, I feel this is more urgent in some fields than others, but I suspect all fields may benefit greatly by moving away from top-down delivery models.

Universities need to be comfortable and safe — and I think this should go without saying, but universities need to attend to this more. Being among Arthur Erickson’s buildings at SFU makes me feel that I’m in some sort of retro-future. I appreciate the transparency of purpose these buildings provide, but they’re cold, authoritarian, and incredibly hard to rethink. At the same time, they are designed to serve interdisciplinary roles and bring people together. Many institutions face the same situation.

I think there is still tremendous value in these buildings. The challenge for a design team is how to plan for futures where these designs can still be relevant — toward serving transdisciplinarity and post-disciplinary scholarship and discovery. This reflects a sort of fluidness that enables natural human movement and thought among disciplines. At the same time, these spaces must also attract and honor the community (esp. including first peoples), including cultural-relevant spaces and ceremonial spaces. Put simply, the architecture of future-oriented universities adopt needs to reflect and engage with ‘humanness’ of the university’s mission.

Universities that signify membership create a sense of togetherness. This goes beyond the producer-consumer model that institutions are tempted to adopt where students as treated as customers. This also goes beyond creative branding or displaying the school mascot everywhere.

Spaces that signify membership invite co-ownership, co-creation, and co-responsibility for the success of each other and the institution. Student unions and activity centers are classic examples where this happens in universities, but too often they are turned into food courts and other retail centers. A classic, student union-type experience should not be centered around food courts or specific buildings. They should be threaded throughout campus — and the campus should be designed to be inviting and welcoming to everybody. Most importantly, these spaces need to be inclusive of the entire community the university touches, be it people from the community, international students, immigrants, and first peoples.

The act of being playful is one of the best (and most natural) ways in which we discover and learn. In how many university or department missions do we see the words ‘play’ or ‘fun?’ Free play is a natural human activity where learning flourishes in a very invisible manner. Through play, we discover our interests and aptitudes. Play inspires curiosity to test boundaries and learn social rules and norms, together with the development of many soft skills.

Through play, a learner’s environment becomes his or her laboratory. This satisfaction of curiosity encourages the development of auto-didacticism, the practice of learning by one’s self. This, I believe, attends to transdisciplinary learning... or even post-disciplinary learning (base of knowledge is unique at the individual level).

Similar to free play is free exploration within our own communities and beyond to learn from others. What happens, for example, when we explore a culture beyond our own? What do we discover? How does it change us? What skills, competencies, or insights might we develop? Many of the answers to these questions are difficult to quantify or measure, but research suggests they can be related through the development of soft skills (i.e., intercultural competence, capabilities to handle ambiguity, empathy), which are critical outputs of invisible learning. This is learning beyond codifiable curricula, and places trust in students that they can develop their own skills.

Finally, let’s face it: education is crazy expensive. We need to build affordable spaces wisely. In our question to obtain cost savings, we can feel pressured to ‘engineer’ new spaces rather than ‘design’ them. When we engineer solutions without placing emphases on design first, we risk the danger of having a nice space that works for the moment but is not suitable for the future.

An engineered classroom building is hard to convert to anything else. This is especially important as our conceptualizations of what is a ‘classroom’ may evolve significantly over time. We save in the long term by placing design first.

Universities are human, knowledge-centered enterprises with additional, tremendous costs in facilities and equipment. And, as human-centered organizations, they cannot realize the same savings in cost as institutions in other industries that can leverage technologies to do work, their costs will increase relative to the rest of the economy.

The jobs we will take on in the future are the ones that robots and software cannot do. Knowmads navigate this challenge well. My perspective is that we should look hard into taxing industries that are able to eliminate humans from their workforce, leveraging cost savings through technologies to subsidize education and human development for training and retraining, as necessary.

In lieu of conclusion…

As we look toward the future, the question for university communities everywhere is, can we transform our campuses to remain relevant for the next 50 years? In a technology-driven world, what can the university do that technologies cannot replicate?

References

Moravec, J. W. ( Ed.) (2013). Knowmad Society. Minneapolis: Education Futures. ISBN (print edition): 978-0615742090

Noriega, F. M., Heppell, S., Bonet, N. S., & Heppell, J. (2013). Building better learning and learning better building, with learners rather than for learners. On the Horizon, 21(2), 138–148.

Schwartz, P., & Ogilvy, J. A. (1979). The emergent paradigm: Changing patterns of thought and belief. Menlo Park, CA: SRI International.

Image credits

Festival photo by Krists Luhaers on Unsplash.

Education Futures LLC

+1 612-234-1231

hello@educationfutures.com

Subscribe to our newsletter

Follow us on: LinkedIn | Facebook